Mentoring girls in sports

This post is part of a "series" I am doing in which I comment on some of the articles in the most recent edition of The Scholar and Feminist Online whose theme was The Cultural Value of Sport: Title IX and Beyond.

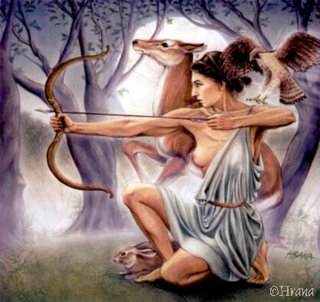

In my first post, I commented on Catherine Stimpson's address about the Atalanta Syndrome. In this one I turn to the essay by Margaret Carlisle Duncan entitled "The Promise of Artemis." I have liked that many of the authors have continued to employ mythological analogies as they respond to Stimpson's lecture. Duncan invokes Artemis, the woman/goddess who raised Atalanta after her father ditched her in the woods. Artemis taught Atalanta the skills--mental and physical--that she took back with her to her father's kingdom where she engaged in the foot races for which she is best known. (Alas Artemis did not teach her how to avoid the temptation of the golden apple--apples seem to be the downfall of many a woman in pagan and Christian mythology.)

The figure of Artemis, Duncan says, is much needed in the world of youth sports to serve as role models and mentors. Arguing that "socialization is a two-way street," Duncan says that Artemis(es) praise girls for their particpation in sport and physical activity. This stands in contrast to more typical methods of socialization in which girls are praised for conforming to hegemonic femininity.

An Artemis is also able to help girls negotiate the "contested terrain" that is sport and the moment in lives of many sporting girls when being a "tomboy" is no longer acceptable.

But Duncan spends most of article critiquing the most prevalent source of physical activity in the lives of girls: physical education. And she offers suggestions for reforming PE to be more inclusive and supportive of girls including lessening the focus on "the kinds of sports that are celebrations of masculinity." In part taking the focus off sports such as football, baseball, basketball, which many boys already have skills in (because of extracurricular particpation) would alleviate the widening gap between girls' and boys' physical abilities that also serves to reinforce the belief the girls are less athletic.

Duncan provides two responses, one liberal, one radical, to the problems girls encounter in the world of institutional sport and physical activity. In her liberal response Duncan calls for, among other things, the identification of Artemises at all levels of programs and government (in the forms of parents, teachers, administrators and athletes "who have bucked the system") who could serve as advocates for girls' programs.

Though she does not mention Title IX here, I would suggest that advocates at all levels will be especially important in future fights for the protection and expansion of Title IX. People who have worked with girls and supported their endeavors in sports and other physical activities will be more likely to rally against potential harmful changes and interpretations in the law. It is also possible that the growth of a cadre of Artemises might put enough pressure on administrators to effect change without lawsuits.

In her radical response, Duncan suggests (or rather passes on the suggestion of other scholars)that girls should "set the agenda for physical education." This is a suggestion that practitioners of feminist pedagogy (outside the PE "classroom") have advocated as well. I have experimented with it myself--though minimally--in college classrooms and found it worthy of future consideration. There is, of course, the need to balance what students say they want to learn and what we, as educators, believe they should know.

But I believe Duncan (and the scholars she cites) are correct in their asseessment that girls will tell you what they want to know about their bodies and their capabilities given the right environment.

Duncan ends her essay beautifully so I will simply use her words to end this post:

"Sport is the field on which gender battles are fought. The stakes at the material level may seem trivial, but the stakes at the symbolic level are not. These symbolic stakes include the empowerment of girls, the cessation of assualts on female subjectivity, and the end of the assumption of female inferiority and male superiority."

Comments